August 2021

Frances Verter, PhD

Cell therapy to restore fertility is an active area of research in some countries. Dr. Verter reviewed 5695 clinical trials of advanced cell therapy from the CellTrials.org database covering the years 2011 to 2020, and extracted 112 trials which specifically target medical diagnoses that impact fertility. The male issues included are: erectile dysfunction, Peyronie’s disorder, and low sperm count (azoospermia). The women’s issues cover ovarian insufficiency and multiple disorders of the uterine lining (endometrium), including: thin endometrium, implantation failure during assisted reproduction cycles, intrauterine adhesions, and Asherman’s syndrome. Excluded were all disorders of the urinary tract, male or female.

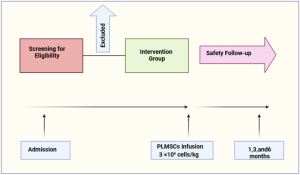

The first two figures show how the complete set of 112 trials break down in terms of number per year and fraction devoted to the major diagnostic categories.

In the remainder of this article we will focus on the 49 clinical trials registered from 2011 to 2020 that employed cell therapy to regenerate the endometrium of infertile women. This field owes its launch to a provocative paper published in 2004 which examined the endometrial biopsies from a handful of women who were bone marrow transplant recipients, and found that donor-derived cells accounted for close to half of epithelial cells and stromal cells in their biopsy samples1. Subsequent efforts to repeat that study found donor cell levels below 10%2, but enthusiasm to regenerate the endometrium with cell therapy had been ignited. Stem cells unique to the endometrium were first identified in 2004 and have potential as a tool for regenerative medicine3. In practice, we find that to date only two clinical trials claim to have harnessed endometrial stem cells for the treatment of the uterine lining.

In 2011, a ground-breaking case report was published that described a cell therapy success for a woman with Asherman’s syndrome4. In Asherman’s syndrome, the uterine lining is completely replaced by fibrotic tissue and adhesions. Between 2% and 22% of infertile women suffer from intrauterine adhesions, with geographic variations depending on the incidence of diseases and medical practices that might injure the endometrium2. The conventional treatment of Asherman’s syndrome is to remove the adhesions by hysteroscopic adhesiolysis and follow up with hormone therapy. However, about half of Asherman’s patients fail to achieve pregnancy after conventional therapy5. The woman in the 2011 case report had her own bone marrow stem cells implanted into her uterine cavity during fertility treatments, and after this intervention she became pregnant4.

Since then, a number of academic centers and fertility clinics have been incorporating cell therapy into fertility treatments for women that have a thin or scarred uterine lining. The second pie chart shows the categories of cell types that have been employed in clinical trials of cell therapy for the uterine lining. The average target enrollment among these clinical trials is 76 women, with a range from 10 to 500 patients. A literature review and meta-analysis released in late 2020 found that 8 peer-reviewed articles had been published about controlled trials of cell therapy to treat Asherman’s syndrome5.

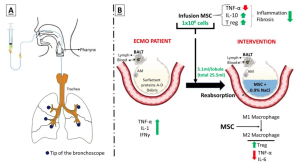

Clinical studies have demonstrated that implanting stem cells into the uterus increases the endometrial thickness, to a statistically significant extent5-14, and for a prolonged period of time14. Hence, the treatment works, regardless of uncertainty over the mechanism of action. In fact, the efficacy of this cell therapy greatly exceeds the possible engraftment of stem cells, which leads to the argument that paracrine effects must play a dominant role. This was confirmed by groups that compared gene expression between their before and after biopsies10,15.

The bottom line is that women who did not respond to conventional treatments have become pregnant and delivered babies after cell therapy to increase the thickness of their uterine lining.4,7-10,13,14

But much more work remains to be done in this field. There are enormous variations in the exact techniques used from one clinical trial to another. Parameters that vary between studies include the type of cells, the processing of the cells, the cell dose, the concomitant medications and surgical procedures, etc. etc. Even studies that rely on mononuclear cells (MNC) may select for MNC with different markers.

Most researchers would agree that the goal of transplanting stem cells into the uterus is to have them take up residence in the basal layer of the endometrium, but the specific routes of administration used to deliver the cells also vary widely among clinical trials. One method of delivery is to infuse the cells into the spiral arterioles, which are small arteries that supply blood to the endometrium. Most of the trials inject the cells directly into the endometrium during a hysteroscopy. A more elaborate method used by 11 of the 49 clinical trials is to load the cells into some type of matrix (typically a collagen scaffold), and then transplant this patch of engineered tissue into the uterine lining.

In the past, women with intractable infertility have often turned to surrogate mothers to carry their pregnancy. However, surrogacy is a very expensive option and is fraught with many legal and ethical complexities. More countries are prohibiting parents from hiring commercial surrogates16. Under these circumstances, research on restoring women’s fertility takes on new urgency. Cell therapy of the uterine lining has the potential to be less expensive and more accessible than surrogacy, if it can transition from clinical trials to approved therapies that are open to the general public14,16.

References:

- Taylor HS. Endometrial cells derived from donor stem cells in bone marrow transplant recipients. JAMA 2004; 292(1):81–85.

- Gargett CE, Schwab KE, Deane JA. Endometrial stem/progenitor cells: the first 10 years. Human Reproduction Update 2016; 22(2):137–163.

- Chan RW, Schwab KE, Gargett CE. Clonogenicity of human endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biology of Reproduction 2004; 70(6):1738-1750.

- Nagori CB, Panchal SY, Patel H. Endometrial regeneration using autologous adult stem cells followed by conception by in vitro fertilization in a patient of severe Asherman’s syndrome. J Human Reproductive Sciences 2011; 4(1):43-8. [cells from autologous bone marrow]

- Zhao Y, Luo Q, Zhang X, Qin Y, Hao J, Kong D, Wang H, Li G, Gu X, Wang H. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Stem Cell-Based Therapy in Treating Asherman Syndrome: A System Review and Meta-Analysis. Stem Cells International 2020; 2020:8820538 [review & meta-analysis]

- Singh N, Mohanty S, Seth T, Shankar M, Dharmendra S, Bhaskaran S. Autologous stem cell transplantation in refractory Asherman’s syndrome: a novel cell based therapy. J Human Reproductive Sciences 2014; 7(2):93–98. [cells from autologous bone marrow]

- Santamaria X, Cabanillas S, Cervelló I, Arbona C, Raga F, Ferro J, et al. Autologous cell therapy with CD133+bone marrow-derived stem cells for refractory Asherman’s syndrome and endometrial atrophy: A pilot cohort study. Human Reproduction 2016; 31(5):1087–1096. [cells from autologous apheresis]

- Tan J, Li P, Wang Q, Li Y, Li X, Zhao D, Xu X, Kong L. Autologous menstrual blood-derived stromal cells transplantation for severe Asherman’s syndrome. Human Reproduction 2016; 31(12):2723–2729. [cells from menstrual blood]

- Zhao G, Cao Y, Zhu X. et al. Transplantation of collagen scaffold with autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells promotes functional endometrium reconstruction via downregulating ΔNp63 expression in Asherman’s syndrome. Science China Life Sciences 2017; 60(4):404–416. [cells from autologous bone marrow]

- Cao Y, Sun H, Zhu H. et al. Allogeneic cell therapy using umbilical cord MSCs on collagen scaffolds for patients with recurrent uterine adhesion: a phase I clinical trial. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2018; 9:192 [umbilical cord MSC]

- Azizi R, Aghebati-Maleki L, Nouri M, Marofi F, Negargar S, Yousefi M. Stem cell therapy in Asherman syndrome and thin endometrium: Stem cell- based therapy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018; 102:333-343. [review]

- Lee SY, Shin JE, Kwon H, Choi DH, Kim JH. Effect of autologous adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction transplantation on endometrial regeneration in patients of Asherman’s syndrome: a pilot study. Reproductive Sciences 2020; 27(2):561–568. [autologous adipose SVF]

- Ma H, Liu M, Li Y. et al. Intrauterine transplantation of autologous menstrual blood stem cells increases endometrial thickness and pregnancy potential in patients with refractory intrauterine adhesion. J Obstetrics Gynaecology Research 2020; 46(11):2347–2355. [cells from menstrual blood]

- Singh N, Shekhar B, Mohanty S, Kumar S, Seth T, Girish B. Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cell Therapy for Asherman’s Syndrome and Endometrial Atrophy: A 5-Year Follow-up Study. J Human Reproductive Sciences 2020; 13(1):31-37. [cells from autologous bone marrow]

- de Miguel-Gómez L, Ferrero H, López-Martínez S, Campo H, López-Pérez N, Faus A, Hervás D, Santamaría X, Pellicer A, Cervelló I. Stem cell paracrine actions in tissue regeneration and potential therapeutic effect in human endometrium: a retrospective study. BJOG 2019; 127(5):551-560.

- Bagri/Anand NT. A Controversial Ban on Commercial Surrogacy Could Leave Women in India With Even Fewer Choices. TIME Magazine Published 2021-06-30

Source: Parent’s Guide to Cord Blood