Ottawa Citizen , Jan 18 2024

Ottawa research aims to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a chronic lung disease that afflicts many premature babies.

Emmy Cogan was 10 days old when she made history. Last March, the Ottawa micro preemie, who weighed just over 500 grams at birth, became the first baby to take part in a world-first clinical trial aimed at minimizing the health challenges that often accompany very premature birth.

Her parents did some soul-searching before agreeing to sign her up for the clinical trial. Did it make sense to enrol their tiny, fragile daughter in a clinical trial for a stem cell-based treatment that had never been tested on humans? At the time, Emmy was hooked up to a ventilator at The General campus’s neonatal intensive care unit and was so fragile that her parents were not allowed to hold her.

Alicia Racine and Mike Cogan talked to family and friends, including those with medical backgrounds. The response was overwhelmingly positive. Before making a decision, they also spent a long time with Dr. Bernard Thébaud, the neonatologist and senior scientist at The Ottawa Hospital and CHEO who is leading the research.

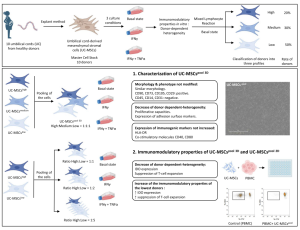

Still, when it came time for the procedure last March, in which a solution of stem cells retrieved from umbilical cords was infused into Emmy’s bloodstream, Racine and Cogan were nervous — at first.

Cogan said he relaxed when he realized it wasn’t much different from other procedures Emmy had undergone since her birth at just over 23 weeks’ gestation. These had included multiple blood transfusions. In some ways, it was like any other day.

But not for Thébaud. The professor of pediatrics at the University of Ottawa has devoted much of his career to finding a way to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a chronic lung disease that afflicts many premature babies. March 3, 2023 was a landmark day toward reaching that goal.

“It was a very emotional moment,” Thébaud said.

As he stood by Emmy’s isolette waiting for the stem cell treatment to be infused into her bloodstream, a nurse asked whether Thébaud would like to start the pump setting the procedure into motion.

“I realized all of a sudden that 20 years of work had gone into this. I tried to hold it back, but I did shed a few tears.”

The procedure went as planned and Emmy is thriving, despite her early start. She was born so early, after Racine’s water broke while on the job as a 911 operator for Ottawa Police, that she was considered just on the edge of viability. That hasn’t stopped her.

“She was always a mover and hasn’t slowed down,” said Cogan, a mechanic with Waste Management and Waste Connections of Canada. “She is a wiggler and is full of smiles.”

Emmy, short for Emerson, left the hospital on July 6, more than four months after her birth. She was on oxygen day and night for the first month at home and continued to be hooked up to oxygen overnight for a few more months.

“Other than that, she doesn’t have any health issues,” said Cogan. “She seems like a regular baby.”

She now weighs 15 pounds and is meeting all of her milestones. “She rolled over when she was supposed to roll over and is trying to stand now,” said Racine.

Emmy was the first baby enrolled in phase one of the clinical trials, which aimed to determine the safety of the treatment. By November, nine babies had been part of the trial, said Thébaud.

In order to qualify, babies had to be born before 28 weeks’ gestation — the tiniest preemies — and had to still be on a ventilator at one week after birth. All of the babies would, therefore, be at high risk of developing moderate to severe BPD, he said.

The babies will be evaluated at 24 months, but so far, he said, everything has gone well “and we are very confident we can move forward to a phase two.”

One hundred and sixty eight babies will be enrolled in the second phase, a randomized control trial. Some babies will be given the treatment and some will be given a placebo. Researchers will not know which babies received the treatment and which didn’t when they assess their progress. Among measures of success will be how early babies can be taken off mechanical ventilators after receiving the treatment. The second phase is expected to take three years.

“My hope is that phase two will show those babies who received the cells will have improved lung and brain outcomes,” Thébaud said. His goal is for the treatment — if the trials are successful — to become a standard of care for very premature infants to prevent BPD, which can seriously impact children’s growth and development.

“Within three years, we should know if this works or not.”

Thébaud’s team is not the only one in the world working on a stem cell-based treatment to prevent BPD in premature infants. That, he hopes, will boost the chances of it becoming a viable treatment for the 1,000 babies who get BPD every year in Canada.

“It would be a big splash, a big game-changer for these babies.”

Having parents step up and enrol their babies, starting with Emmy, was key to evaluating the treatment that could eventually help thousands of babies live healthier lives.

Thébaud and his team worked hard to inform and answer questions parents might have, including creating an animated video to explain the procedure and the research goals.

Emmy and the babies who were part of the first phase of the trial will not undergo the same detailed assessment to determine whether the treatment works, but Racine and Cogan are still hoping it will be beneficial.

“We wanted to give her all the chances to be healthy,” said Racine.

Cogan said he is grateful they live close enough to The Ottawa Hospital to have been able to participate in the trial.

“This was a very positive experience for us. When these opportunities are presented to people, it is important to … really give it some thought.”

Ten months after she received the treatment, Emmy’s parents have other things on their minds, though, including planning a big first birthday party for her and inviting family members who were unable to see her for so long while she was in the hospital.

Source: Ottawa Citizen